Fellow member of Women Writing the West, Alethea Williams is the author of Willow Vale, the story of a Tyrolean immigrant’s journey to America after WWI. Willow Vale won a 2012 Wyoming State Historical Society Publications Award. In her second novel, Walls for the Wind, a group of New York City immigrant orphans arrive in Hell on Wheels, Cheyenne, Wyoming. Walls for the Wind is a WILLA Literary Award finalist, a gold Will Rogers Medallion winner, and placed first at the Laramie Awards in the Prairie Fiction category.

Fellow member of Women Writing the West, Alethea Williams is the author of Willow Vale, the story of a Tyrolean immigrant’s journey to America after WWI. Willow Vale won a 2012 Wyoming State Historical Society Publications Award. In her second novel, Walls for the Wind, a group of New York City immigrant orphans arrive in Hell on Wheels, Cheyenne, Wyoming. Walls for the Wind is a WILLA Literary Award finalist, a gold Will Rogers Medallion winner, and placed first at the Laramie Awards in the Prairie Fiction category.

“In sofar as the taking of captives and reducing them to slaves was concerned the Apache acquired this custom from the Spaniard or Mexican, and it is safe to say that during the period of which I write there was not a settlement in the valley of the Rio Grande that did not number among the inhabitants a large number of Apache and Navajo Indian slaves.”

—Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The Leading Facts of New Mexican History, Torch Press, 1917

The primary female character in my novel, Náápiikoan Winter, is abducted as a child and later traded into slavery. She is abducted by Apaches, sold by Utes, and enslaved by other tribes including the Piikáni. Was it true that Native Americans learned this practice from contact with the Spaniards, as the quotation that opens my book asserts?

Although it’s true Christopher Columbus started an unholy tradition by enslaving over 500 Indians, an article on the website Oxford Research Encyclopedia: American History by Christina Snyder says, “The history of American slavery began long before the first Africans arrived at Jamestown in 1619. Evidence from archaeology and oral tradition indicates that for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years prior, Native Americans had developed their own forms of bondage.” Indians captured women and children to replace the up to 90% of their people killed by war and diseases they had no defense against. In an article for Slate, Rebecca Onion says “Native types of enslavement were often about kinship, reproductive labor, and diplomacy, rather than solely the extraction of agricultural or domestic labor.”

All Native tribes that I know of were called “The People.”

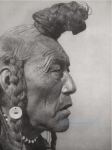

photo of a Blackfoot by Edward Curtis, hairstyle described in Naapiikoan Winter as a similar one worn by the character Saahkómaapi (Young Man), Beaver Bundle Man to the Inuk’sik band of the Piikáni, the band’s Dreamer

What this common nomenclature implies is that the people of one’s tribe were People, and all others were something less. Captives were outside society, but slaves were even further outside the social order. So as a slave passed from tribe to tribe, my character Buffalo Stone Woman would have had many instances of rejection and neglect. For most of her adult life, she would not have been accepted by anyone as a true person, but a creature somewhere on a level with a dog or other tamed animal.

There were ways to escape the status of captive, enshrined in solemn ceremony, that could make of a mere captive a real person by adoption or marriage. Slaves were of a different nature, “distinguished by the extremity of their alienation from captors’ societies and the exploitation of their labor to enhance the social or material life of the master,” according to Snyder. Slaves often had a lot of freedom to come and go in the performance of their duties. And slavery wasn’t a hereditary condition: children of Indian slaves were not themselves enslaved.

So in Náápiikoan Winter, when Buffalo Stone Woman finds a home at last among the Piikáni at the base of the Rocky Mountains where although a slave she has attained the status of a distant wife to the powerful Orator, she wants never to have to leave this safe haven. She is tolerated, even accepted. She brings to her new people her skills and her knowledge, which makes them, already powerful, an even more potent force on the Plains.

Alethea has graciously agreed to give away one copy of Náápiikoan Winter to one person who leaves a comment. And the winner is Barbara Bettis. Congrats!

At the turn of a new century, changes unimagined are about to unfold.

At the turn of a new century, changes unimagined are about to unfold.

THE WOMAN: Kidnapped by the Apaches, a Mexican woman learns the healing arts. Stolen by the Utes, she is sold and traded until she ends up with the Piikáni. All she has left are her skills—and her honor. What price will she pay to ensure a lasting place among the People?

THE MAN: Raised in a London charitable school, a young man at the end of the third of a seven year term of indenture to the Hudson’s Bay Company is sent to the Rocky Mountains to live among the Piikáni for the winter to learn their language and to foster trade. He dreams of his advancement in the company, but he doesn’t reckon the price for becoming entangled in the passions of the Piikáni.

THE LAND: After centuries of conflict, Náápiikoan traders approach the Piikáni, powerful members of the Blackfoot Confederation. The Piikáni already have horses and weapons, but they are promised they will become rich if they agree to trap beaver for Náápiikoan. Will the People trade their beliefs for the White Man’s bargains?

Excerpt: CHAPTER 1

ISOBEL, A LIGHT SLEEPER, woke in darkness to the sounds of her parents’ habitual nighttime dispute.

“Will you do nothing? Stupid, lazy bitch! No better than a dog in heat—you breed bastard children from different men and leave them to raise themselves. You’re like a mangy cur bitch on a leash of gold. I wish I’d never set eyes on you!”

Graciela, Isobel’s mother, said something too low for the child to decipher.

In reply, Isobel’s father, Armando, growled, “It won’t work this time, Graciela. Have you no pride? You resemble the commonest prostitute on the streets of Cádiz!”

To purchase Náápiikoan Winter, go to http://www.amazon.com/Naapiikoan-Winter-Alethea-Williams-ebook/dp/B01EIQNCMO/ http://www.amazon.com/Naapiikoan-Winter-Alethea-Williams/dp/1532710569 https://www.createspace.com/5786432 http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/naapiikoan-winter-alethea-williams/1123779705

To find out more about Alethea and her books, please go to

An interesting aspect of Native American culture that is seldom portrayed in fiction. Isabel’s father clearly has no idea what type of adventure await’s her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for hosting Naapiikoan Winter on your site!

LikeLike

My pleasure Alethea. Truly fascinating post. Thanks for being my guest

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting, Brigid. I hope if you’re reading Naapiikoan Winter that you’re enjoying the story and will consider leaving a review on Amazon and/or Goodreads.

LikeLike

This was fascinating. Thanks for the illumination.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for stopping by, Charlotte. The research for this book was truly absorbing so I’m glad you liked the essay.

LikeLike

I’m writing a novel set in the Chickasaw Nation in 1820, today’s northern Mississippi. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, the Chickasaw, Choctaw and other tribes took captives from enemies and traded them to English, French, and Spanish colonists. After American independence, most tribes held African slaves as a means of advancing economically against the US slave societies. Escaping slaves made their way into Indian country seeking freedom, but usually found bondage instead. When the tribes were removed west of the Mississippi River, they took their African slaves with them. These slaves were not impacted by the Emancipation Proclamation nor the 13th Amendment. They were freed in separate agreements with the US Government in 1866.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating! Thanks you SO much for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How long have you been researching slavery among the Chickasaw and Choctaw, David? Let me warn you, it easily becomes addictive! Your book sounds fascinating; I will look forward to its publication.

LikeLike

What a wonderful post. Your excerpt was so compelling, Alethea! David’s comment was intriguing, as well!! Best of luck with the book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for visiting Andi’s blog, and for commenting, Barbara. And thanks so much for the good wishes!

LikeLike

An intriguing theme and interesting story. Looking forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for commenting, Teresa. Good luck in winning the giveaway for Naapiikoan Winter, and I hope you like it when you get a chance to read it.

LikeLike

Your interview was so informative! Your book sounds like it will be an emotional roller coaster and a fascinating read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for commenting, Linda, and for your accurate insight of the emotional turmoil in Naapiikoan Winter. I’m glad you liked my essay and found it informative.

LikeLike

Wonderful story and essay. I write about the Mission Indians of California. In my upcoming release Maria Ines. The relationship of church and Indian is complicated. I appreciate your research. A worthy contribution to women’ s fiction of the West.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Anne. I read Cholama Moon after attending the WWW conference in Golden. I also appreciate the research that goes into a good historical novel, and your kind comments.

LikeLike

Slavery has been a part of every culture from the beginning of time. Your book sounds great, Althea.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find it more than curious that American Indian history has never become part of “American” history. Mention slavery in America and only African slavery ever comes to mind. In the recent tragedy in Orlando, I read more than once that it was the “biggest” mass slaying ever, as if the U.S. cavalry massacres of Native American camps never occurred, and as if one mass murder can be compared to another. Thanks for commenting, and for your good wishes.

LikeLike

An uncomfortable subject, but one that can’t be swept under a rug. Thank you for researching and telling a story that should add to our knowledge of what life was like during those early years of ‘exploration’.

Congratulations.

Doris

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Doris! As a fellow historical researcher who likes to dig deep, I truly appreciate your support.

LikeLike

Loved the post! I know my Cherokee branch owned slaves before they were moved to Oklahoma in the early 1800s. Great research!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Ilona! I’m glad you liked my slavery essay and can verify the facts from your own family history.

LikeLike

Sounds like a great story and my list grows ever longer. 🙂 You probably know this, but both Sacajawea and Wet-Khoo-Weis who helped Lewis and Clark, one as a guide and one by keeping the Nez Perce from killing them, were captured by other tribes, the latter sold, and traded until she, like Sacajawea ended up in the exact place they needed to be to aide those early explorers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Eunice. Thanks for your comment including a bit of Native American slave history that I and perhaps other readers did not know. I hope you get to read Naapiikoan Winter from your TBR list one of these days!

LikeLike

When Lincoln “freed” the slaves, he purposely excluded Mexican and Indian slaves from the Emancipation Proclamation because he wanted to keep the far western states from leaving the union over the issue. The life of peons on the large rancheros was no different than that of Negros in the South.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frank, thanks for the information. You might be interested to know the first part of Naapiikoan Winter is called “Nuevo Mexico,” where young Isobel is first captured by the Apaches and later sold into slavery by the Utes. Life was harsh for the peons and Indian slaves under the Spanish not only on the rancheros, but also in the silver mines, another topic addressed in my book. If all of you who have taken the time to comment get a chance to read Naapiikoan Winter, I hope you enjoy it and will consider leaving a review.

LikeLike

Great writing in that sample. Growing tension. Childhood wonder. Many questions that need answers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope this small excerpt and the essay serve to help readers remember the book so they will add it to their TBR lists. Thanks for commenting, and good luck in the drawing.

LikeLike

Fascinating post. I’m really looking forward to reading this book. Thank you, Andi and Alethea. Every day I learn something new about the West is a good day!

Kelly

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for commenting! I’m glad the essay on Native American slavery gave you some new information, and hope you will get to read Naapiikoan Winter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Concise and well-researched piece. Thank you for this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting! I’m glad you liked the post.

LikeLike

This book sounds really interesting as I am currently researching my ancestry of Afican and Native American descent and trying to find out the truth in some much different stories and information. I would love to know what resources did you use to learn about this form of slavery? I look forward to adding your book to my discoveries!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, thanks for your interest in Naapiikoan Winter. Most of the sources I used to research the novel are listed in the back of the book, but unfortunately by no means all as it was written over the course of 20 years and I neglected to list every book I read in conjunction with the writing. Information on Native American slavery is readily available on the internet, which I find most helpful as a jumping off point, consulting the authors blog posters use as sources for their material. It looks like David Wilma, who posted above, is researching the very area you are asking about. Maybe you could consult him for a few leads.

LikeLike