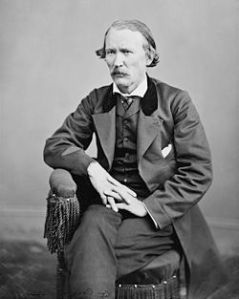

I met Steven Kohlhagen through the American Westerns group of Goodreads. Steve kindly complimented me on the article I had written regarding posterity and memoirs, one of which was Buffalo Bill Cody’s Story of the West. Steve’s latest book, Where They Bury You, partially concerns Kit Carson, and Carson was one of the men Cody had memorialized. Carson’s scorched earth policy, used to remove the Navajo from their homeland, is something that, today, denigrates the man’s other accomplishments as a frontiersman. Yet, Cody claimed that the policy had actually saved lives. I therefore approached Steve to find out what his own research had uncovered.

partially concerns Kit Carson, and Carson was one of the men Cody had memorialized. Carson’s scorched earth policy, used to remove the Navajo from their homeland, is something that, today, denigrates the man’s other accomplishments as a frontiersman. Yet, Cody claimed that the policy had actually saved lives. I therefore approached Steve to find out what his own research had uncovered.

Kohlhagen is a former economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, a former Wall Street investment banker, and is on several corporate boards, most notably that of Freddie Mac. He is the author of numerous economics publications as well as co-author of a murder mystery, Tiger Found, with his wife, Gale.

The Kohlhagens divide their time between homes in the San Juan Mountains on the New Mexico-Colorado border and Charleston, South Carolina.

Flash back 151 years to February 1863.

At that time Kit Carson was a bona fide American hero. It’s right there in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick: frontiersman, mountain man, Indian fighter. He was also a hero of the Mexican-American War, “Father Kit” to the Ute and Apache Indians on his Agency, fictional hero-savior to any number of innocent women and children in distress in the 19th Century “Blood and Thunder” dime novels, and loving Taos father and husband to, over time, two Indian wives.

On the other hand, the Navajo Indians—the Dine—were friendless throughoutthe West. Ill-treated by the Spaniards in the preceding centuries, the Navajos discriminated against no one in robbing, pillaging, murdering, and enslaving women and children. The Dine succeeded in the seemingly impossible: uniting Whites, New Mexicans, Pueblo Indians, Cheyenne, Utes, Mexicans, and all manner of Apache tribes in their hatred and fear of marauding Navajo warriors. Even the Navajo headsmen, when confronted with the opportunity to bring peace, admitted that it was beyond their power to stop their young men from raiding. They essentially responded to attempts by the U.S. Army to enlist their support with the 19th Century equivalent of “Kids today!”

What about 2014? The general view of the Navajo today is one of a venerable, peaceful Native American culture. A spiritual nation inhabiting their Reservation on their native lands in northern Arizona. A people that, to this day, largely view Kit Carson as a genocidal murderer of innocent Navajo.

And, if asked to name great American frontiersman, very few Americans get to Kit Carson’s name.

What happened during the intervening 150 years to bring about this 180-degree switch?

My first introduction to the legend of Kit Carson was by a young Navajo guide on a private tour of Canyon de Chelly. He took me to a medium-high, cylindrical hill covered with brush and small trees deep in the canyon and said, “That’s where Kit Carson brought the Navajo women, children, and elderly and massacred them.” Years later, a friend told me of his tour of the Canyon and the story he’d been told of the massacre there by the Spaniards centuries before Kit Carson. And then I read Hampton Sides wonderful Blood and Thunder. That book launched me into research into the history of the Southwest. A passage in it inspired me to write my own novel, Where They Bury You, a murder mystery based on the actual 1863 murder of Joseph Cummings, U.S. Marshal of Santa Fe and Army Major reporting to Carson.

Six or seven generations of Navajo oral history about the horrible 1860’s “Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo has left many, if not the majority, of living Navajo believing that Carson was responsible.

The truth is that Bosque Redondo was the misguided vision and policy of one General James Henry Carleton, head of the Union Army in the Territories. When the Civil War battles ended in the New Mexico and Arizona Territories in 1862, the Navajo and Mescalero Apaches continued raiding and killing, and in the case of the Navajo, enslaving the local New Mexican people. Carleton decided the only answer was to round them up and deport them to Bosque Redondo, a totally inappropriate section of land along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

Carson objected to the policy as untenable and tried to retire to his family and his Ute and Jicarilla Apache Agency. But Carleton insisted that the famous frontiersman carry out this last patriotic duty.

First, Carson induced the Mescalero to surrender and delivered them to Bosque Redondo.

The Navajo turned out to be a bigger challenge. They simply vanished into the deserts and canyons of their homeland. Carson, frustrated by his inability to find the Navajo and their previous refusals to stop raiding and killing the other neighboring tribes and New Mexicans, implemented a scorched earth policy throughout the Dine homeland. It took nine months, but the Navajo people began trickling in and surrendering. Some deaths obviously may have occurred due to the conditions in which the Navajo were then forced to try to survive, but there was never any massacre per se. In fact, Carson, objecting to the 9,000 person four hundred mile walk without adequate support, returned home to Taos for several months. He then insisted on being the Indian Agent at Bosque Redondo in a failed attempt to help the Navajo adjust to their new home.

Bosque Redondo was a colossal failure. The Mescalero just up and left one night in 1865 to return to what continues to be their home near Ruidoso, New Mexico. The Navajo negotiated their departure and walked the four hundred miles back home in June 1868, one month after the 55 year old Carson died in Taos.

At the time, General Carleton was blamed for the failure and returned to his Texas home to die in relative obscurity in 1878. The Navajo, though, have never stopped blaming Carson for their hardships and deaths. Today, the Navajo story and memory of Carson’s culpability resonates better in the public American culture, while the numerous Navajo depredations and Carleton’s miserable failure have long faded into history. In contrast to modern New Mexicans, some modern Native American tribes still do retain a cultural memory of the negative Navajo history.

Justifiable or not, reaction to the Navajo oral tradition had caused Carson to lose his chance to be remembered alongside Davy Crockett and Buffalo Bill Cody and Lewis and Clark as a first string All-American legend.

How he actually felt about the Indians is best expressed by Carson himself.

When the truly despicable Methodist Minister and commander of the Colorado Volunteers, John Chivington, massacred the elderly, the women, and children at the Cheyenne village at Sand Creek in 1864 while their warriors were out hunting, Carson was asked to testify at the resulting Congressional inquiry. He testified:

“Jis to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws, and blew the brains out of little innocent children. You call sich soldiers Christians, do ye? And Indians savages? What der yer ‘spose our Heavenly Father, who made both them and us, thinks of these things?

“I tell you what, I don’t like a hostile red skin any more than you do. And when they are hostile, I’ve fought ’em, hard as any man. But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who would.”

***********************************************************************

Steve was inspired to write his latest novel after reading Hampton Sides‘ wonderful Blood and Thunder. This non-fiction history of Kit Carson and the West includes a report of the factual murder of Marshall Joseph Cummings on August 18, 1863, and led Kohlhagen to conduct further research, including work at the National Archives. He found Carson’s explanation for Marshal Cummings’ murder to be implausible. The result is his historical murder mystery, Where They Bury You.

Steve has very kindly offered to give away one autographed copy of Where They Bury You to someone leaving a comment. The winner is Paul Colt. The book can also be purchased at http://www.amazon.com/Where-They-Bury-You-Novel/dp/0865349398/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=1-1&qid=1389914377

Steve can be found at:

http://www.amazon.com/Steven-W.-Kohlhagen/e/B00E5LZ0B4/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0

https://www.facebook.com/SteveKohlhagenAuthor

https://www.facebook.com/stevenw.kohlhagen

Fashions in political correctness will make a villain of practically anyone – even wrongfully, given the passage of enough time.

LikeLike

Interesting view, Celia. I wonder if it’s fashions in p.c. or changes in civilization–and perhaps they’re related. Thanks for commenting!

LikeLike

Thanks for the “correct” thoughts. Celia. No reason why we would expect combatants histories to be fair to each other, of course. Thanks, swk

LikeLike

Great post Steve. Not surprising Navajo oral tradition comes down on a different Carson than the historical record described so well in Blood and Thunder. History is full of this sort of dispute. This one reminds me of the divergent perspectives we have on ‘Greasy Grass’ and ‘Custer’s Last Stand.’ Distortions visible in our historical windows make for great stories. Best of Luck with the book. Good choice Andi.

LikeLike

Thanks Paul!

LikeLike

Thanks for the excellent comments, Paul. Hmmmmmm, I think you might want to look forward to the sequel: “Chief of Thieves.” Takes place in Colorado, Oregon, and Wyoming in 1863-1877. Thanks, swk

LikeLike

I think everyone in our family will want to read Where They Bury You- esp. my teenage son who is into historical mysteries!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the nice thought and your support. Hopefully you have a large family, none of whom like to share their belongings! ;-). Swk

LikeLike

Wow, very interesting. I will have to ask my Navajo friends their take on this piece of history. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Well, that would be very interesting, Carmen. Perhaps you could get them to comment as well?

LikeLike

The vast majority of Navajo have been raised under the oral tradition that Kit Carson committed genocide on their ancestors. All people’s perspectives are valid. Oral histories are communicated by loved ones (in this case six generations) and inherently difficult to amend. I will take to my grave the stories my father and grandfather and uncle and cousins told me of their experiences in 1930’s Germany. There is no way and no incentive for me to refute those stories I heard and then passed on to my children.

LikeLike

Very interesting contradictions, Steven. That’s the thing about history…. It has multiple Points of View. Don’t you just wish you could sit in on a conversation between Carson and Chivington? Great post, Andrea, Steven.

LikeLike

Lol. THAT would have been a VERY short conversation! Could’ve happened if Canby had let Carson take the New Mexico Volunteers to chase the Texans to Glorieta. Thanks. swk

LikeLike

Very interesting “twist” to Kit Carson’s history. I read Blood and Thunder to understand the Navajos I was researching who interfaced with William N. “Navao Bill” Wallace, a trader who lived and worked with Richard “Dick” Simspon of Gallegos Canyon. And those Indians Bill took to Durango were often photographed by my great-grandfather. I also found some disturbing quotes from Bill Cody about Sitting Bull. I would like to know what you have discoverd about William F M Arny and his role in the Long Walk. I will take the time to read what you have posted about Carson. And I will read your book as well.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the illuminating comment. The Long Walk actually was 6 months after the ending of my novel and I must confess that, accordingly, I have not done any research on Arny. He managed to avoid my characters. My loss and now on my to-do list. Thanks so much. swk

LikeLike

What a fascinating post. I always considered Kit Carson one of our Western Frontier heroes without really knowing much about it. And like many, I didn’t realize the Navajo had been a warring people. What I recall from public school American history classes portrayed them, as you said, as peace-loving, artistic people.. I’ll definitely read your book, as well as the one you referenced, Blood and Thunder.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the kind comments. I hope you enjoy reading my story as much as I enjoyed writing it. You’ll LOVE “Blood and Thunder.” swk

LikeLike

Great post, Steve! During my many history researches, I have also learned of the many contradictions, especially where American Indians are concerned. Their oral histories are filled with so much insightful information that we’ll probably not read in our history books, so it takes authors and writers like us to dig through all the contradictory minutia to present a viable story of the truth.

I remember speaking to an Apache father who was just busting to tell me how proud he was that his daughter had reached maturity and her participation in the Corn Dance (if I remember correctly) signified this stage in her life. I was honored he had shared this rite of passage with me.

Bravo! Looking forward to reading your novel!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the addition to this dialogue. There is much to learn about the native american cultures within our midst. Anyone who has NOT been to the NMAI in Washington DC is depriving themselves of a great opportunity. Thank you for the nice story. swk

LikeLike

The trouble is, we judge all the past by our own standards. That makes just about everyone look like villans.

LikeLike

Good Point, Ilona. thanks for stopping by!

LikeLike

Excellent point, Ilona. AND using what we know about how it turned out. Thanks so much. Swk

LikeLike

Andi and Steven,

This is an awesome discussion of how the interpretation of history is shaped by our beliefs, experiences and long oral tradition. In researching history along the US/ Mexican border, I came to see Pancho Villa and Geronimo as more complex characters than tradition relates and so chose to show their more positive attributes. It was a great adventure as a writer. I’ll look forward to WHERE THEY BURY YOU…a captivating title by the way.

Arletta

LikeLike

Thanks Arletta. You are so correct. It is really fun in researching our books to discover these characters more true to themselves than to our needs for legends. swk

LikeLike

Pingback: KIT CARSON vs. JOHN CHIVINGTON: THE TWISTS AND TURNS OF HISTORY | Steven W. Kohlhagen

Those are some pretty sweeping generalizations about Navajo relations to outsiders in there. And the difficulty controlling raiders is hardly unique to the Navajo people. Others raided too. And the U.S. did a piss poor job of controlling squatters heading into native lands. Narratives like this are arbitrary at best. They promote prejudice.

LikeLike

This is Steve Kohlhagen’s reply:

Hey Daniel, thanks so much for your comment. The history of our country in general, and the West, specifically, 150+ years ago is, as we all know, complicated, and brutal. Like today, the vast majority of people back then

wanted to just be left alone to live their lives in peace as best they could. This is certainly true for the Navajo people today and the Navajo people in the 1850’s and ’60’s. Their documented horrible treatment at the hands of the Spanish invaders left them, a proud people, with few choices, all difficult. It is true that in that period in the West, many Native American tribes raided each other as well as the white settlers. And the U.S. Army carried out many incursions on all of them. I certainly have no wish or any intent to create prejudice by describing events of the 1860’s in New Mexico and Arizona territory. Like today the vast majority of Navajo people wanted peace and to be left alone. Unlike today, though, a material percentage of Navajo young men (not unlike other young men of the time in that area) developed a reputation for indiscriminate and widespread raiding among the Cheyene, the Ute, the Jicarilla Apache, and the New Mexicans. I agree that it would be horribly inappropriate for anyone to be prejudiced toward today’s wonderful Navajo Nation because of acts committed during a distressful period over 150 years ago. What happened happened, but you and i agree that there is no reason for excesses a century and a half ago to be used against any modern human beings today.

Best regards and thanks for reaching out, swk

LikeLike

Hey Daniel, an afterthought supportive of your point of view: after General Carleton’s implementation of his heinous Bosque Redondo relocation of the Navajo people, in the mid-1860’s, the neighboring Comanches discovered the Navajos peacefully living on this “reservation.” Their reaction? They attacked them even thought they were defenseless. A difficult, difficult world back then. Again, thanks for your thoughts, swk

LikeLiked by 1 person