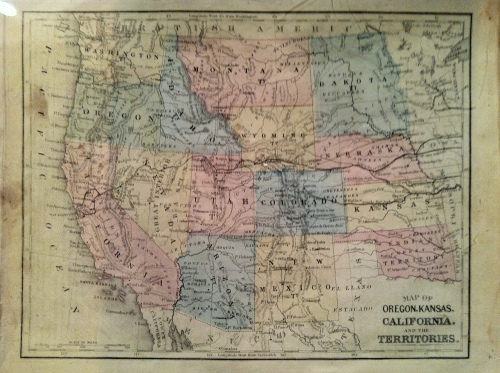

Anyone who read last month’s blog will know I recently acquired an engraving of a Transcontinental Railroad train stuck in a snowdrift. The photo of this is below, in the March post. The 1872 news article accompanying it briefly discussed the various routes that had been considered for the TRR, and this in turn raised a few questions. The article seemed to almost insist that the only point upon which the decision of the route had been based was geography. This didn’t sit quite right with me; I knew from fellow author Paul Colt that shenanigans had surrounded the construction of the TRR, so I turned to Paul to find out more about the decision of the route.

Paul’s book, Grasshoppers in Summer, was a Spur Award Finalist in 2009. It deals with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which ended Red Cloud and the Lakota’s war for the Bozeman Trail. The treaty gave Red Cloud and the Lakotas control of the Black Hills and their Powder River hunting grounds through which ![UnionPacific[1]](https://andreadowning.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/unionpacific1.jpg?w=100&h=150) the Bozeman Trail ran. But Red Cloud’s triumph proved an empty victory once the transcontinental railroad went through a year later, making the Bozeman Trail redundant. Paul’s novel, Case File: Union Pacific, deals more directly with the TRR in that it is based on the Credit Mobilier scandal over the funds for construction of the railroad.

the Bozeman Trail ran. But Red Cloud’s triumph proved an empty victory once the transcontinental railroad went through a year later, making the Bozeman Trail redundant. Paul’s novel, Case File: Union Pacific, deals more directly with the TRR in that it is based on the Credit Mobilier scandal over the funds for construction of the railroad.

So, whom better to ask to do some research on the route of the transcontinental railroad than Paul Colt?![BAND[1]](https://andreadowning.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/band1.jpg?w=500&h=92)

Whither A Transcontinental Railroad?

One of the most enjoyable aspects of writing historical novels is the research. Most fiction writers have experienced some form of the phenomenon where the characters take over and move the story in some unexpected direction. Once in awhile, historical research can also take an unexpected turn.

When Andi first suggested the idea of looking into the politics of choosing a route for the transcontinental railroad, I thought it sounded intriguing. It wasn’t long before I discovered a puzzle full of familiar dots with unfamiliar connections.

I’ve long had a fascination with the transcontinental railroad. In its day it was an engineering achievement of monumental proportions. It played an important part in two of my books. I thought I knew something about this chapter in our history. What I discovered in researching the route selection controversy is what seems to be another of those unexpected historical twists.

The notion of a railway to the Pacific seemed a natural progression in the nation’s manifest destiny as early as the 1840’s. The idea took root following the 1848 acquisition of western territories from Mexico and the discovery of gold in California the following year. The California gold rush in particular highlighted the need. Reaching the nation’s western-most possession could take as much as a year of dangerous overland travel or at best months by sea. As a practical matter there was no way to defend California. A Pacific railroad became a national priority. The question of what route it should take quickly emerged as a lightening rod for political controversy.

In 1853 Congress ordered a survey for the purpose of choosing the most practical and economic rail route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. The War Department commissioned five survey parties. Three parties would proceed west from the Mississippi, exploring alternate routes through the northern plains, central plains to the Rocky Mountains and the newly acquired southwestern territories. Two parties would proceed east from northern and southern California to explore passages to join the westbound routes.

The survey teams finished their work in the fall of 1854. The War Department put forward its recommendation of the southern route preferred by Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis. Northerners in congress thought the recommendation reflected a certain regional bias. In fact, the controversy over which route to select quickly bogged down in differences over the future of slave and free-state territories.

This is where the connections between familiar dots became unfamiliar to me. I never saw the transcontinental railroad as a catalyst for the events that followed. It is possible I dozed off during that American history class in my high school junior year. It was fourth period, right after lunch in a large lecture hall so anything is possible. As I recall, for test purposes, we were more concerned with events and their dates than cause and effect. The controversy stirred up by selecting a route for the Pacific railroad drove straight at the heart of the slavery issue.

At this point it is useful to recall the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The United States had managed to maintain an uneasy balance of power in the Senate between slave and free-states until 1818 when Missouri applied for admission to the union as the twenty third state. Northern interests proposed to ban slavery in Missouri despite the presence of slave holdings in the territory. Southern interests were strongly opposed to any admission that would upset the balance of power in the Senate which protected their longstanding economic interest in the institution of slavery. The issue remained contentious until Maine applied for statehood, at which point both could be admitted, while maintaining the balance of power.

The Missouri Compromise, offered by Henry Clay at the time, sought to put the advance of slavery to rest on some more permanent basis. By its provisions, Louisiana Purchase territories west of Missouri and north of that state’s southern border would be admitted to the union as free-states. Territories south of the Missouri southern border would be admitted as slave states. The effect was to defer for a time territorial disputes over slavery. That equilibrium would necessarily be upset by the routing of a Pacific railroad. Both northern and southern interests rightly reasoned that building the Pacific railroad would spread settlement westward along the rail route and with it the territorial march to statehood.

As eastern railroads built west, they were drawn to favor a central route by

commercial interests in Chicago and Mississippi River commerce concentrated in St. Louis. A central routing clearly favored formation of free-states, thereby putting an end to the Senate balance of power. With antislavery sentiment growing in the north, the south saw such a routing as an existential threat to its economic way of life. No agreement could be reached on a route for the Pacific railroad.

In 1854 Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, proposing creation of two western territories along with repeal of the Missouri Compromise. This created the impression in the minds of Missourians and their southern sympathizers of a return to the balance of power formula for expansion. Northern interests were not fooled. A bitter floor fight ensued. The deadlock was broken by the addition of a ‘Popular Sovereignty’ provision to the act, which allowed inhabitants of the territories to determine the slavery issue. This well intentioned bit of ‘perfectly reasonable foolishness’ enabled Douglas, with the support of President Pierce and southern interests, to pass the bill into law.

When the slavery issue reached the ballot in Kansas, Missourians poured into the state to elect a pro-slavery territorial government over the objection of Kansas residents. This prompted Kansans to elect their own antislavery government. The issue bitterly divided the new territory to the point of bloodshed. Kansas burned as a harbinger to the wider conflict to come.

My historical recollection of that period is framed around John Brown and the abolition issue. I don’t remember the Pacific railroad route contributing to the dispute. Maybe if I lived in Kansas or Missouri I might have gotten a deeper appreciation for the dispute in my American History courses, but I didn’t get that connection from mine. Either I dozed off and really deserved that B, or the connection was overlooked.

The Pacific railroad remained a dusty stack of survey maps until 1861 when the boil that became the war of secession burst. Southern legislators resigned their seats in congress and returned home. Opposition to the central Pacific route disappeared. Union Pacific and Central Pacific proposals for a transcontinental railroad were put forward and approved by Congress in 1862. The Herculean construction effort would not complete until 1869, just in time to bind the nation’s reconstruction in economic union. American commerce and defense could now traverse the continent from Atlantic to Pacific in relative safety and comfort and do so in the breathtaking span of ten days.

Once in awhile, historical research takes an unexpected turn. I’ve had the experience three times in my writing career. All three gave me an idea for a book. Do the politics surrounding the transcontinental railroad route rise to that level? Not for me. Not enough guns, gals and horses for a novel. It’s probably already been done by some serious historian. I am interested to hear what you think. Is the connection between the transcontinental rail route and the slavery issue overlooked; or is it old hat? Either way the research was interesting. Thanks Andi.

Nice article. One of my novels is going to be dealing with decisions and events during the post civil war/reconstruction period and people trying to change some of those events in history. Details like what you shared provide good food for thought, thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

And thanks for stopping by, larry.

LikeLike

Steve,

Thanks for your comment. I hope it helps. The reconstruction period is interesting. I got a background exposure to it from Grasshoppers in Summer. Grant had a running confrontation with Andrew Johnson following Lincoln’s assassination. Grant was bent on enforcing the Reconstruction Acts and Johnson was sympathetic to the unrepentant south. Good luck with your project.

Paul

LikeLike

I don’t think its either overlooked OR old hat. I think there’s potential for a good book set around any historical event that is intriguing to the writer. It’s all about perspective and choices.

LikeLike

Well, I agree. We’ll have to see what Paul thinks. I can see this as a rather good film too, actually…lots of excitement.

LikeLike

Nancy,

Thanks for your comment. For me the route selection issue would be a tough book unless it were set in a larger context like the one Steve is thinking about.

Paul

LikeLike

Thanks! The H/H of my current WIP are taking the transcontinental railroad. This post came at the perfect time! 🙂

LikeLike

Glad we were of service, Dawn!

LikeLike

Dawn,

Glad we could help if we did. Good luck with your project.

Paul

LikeLike

I’ve lived in Kansas nearly forever and don’t recall the railroad being a factor in the dispute, but it might have been. I do a historical kids story for a group of newspapers each year and plan my next one to center around Aug 21, 1863 when Wm Quantrill burned and looted and tried to kill every man and every boy big enough to hold a rifle in that day-long seige. Maybe in my research I’ll pick up some of that railroad dispute. Interesting blog.

LikeLike

Eunice,

Thanks for the insight. I was hoping we would hear from someone with a Kansas perspective. I’m sure some historian has done serious work on the connection between the rail route and the slavery issue. Your observation suggests that for most of us American history education overlooks the causal relationship to the Kansas Missouri border war.

LikeLike

I have used the route of the RR in fiction but never thought past to the politics of what determined which route. I can’t imagine the hardships those five survey team must have endured. Thanks for the information.

LikeLike

Interesting, isn’t it, Linda? And I suspect most people just think the route was determined pure and simply by geography. Thanks for stopping by.

LikeLike

Paul, I call your discovery History Mysteries. Just love a good mystery. Enjoyed the article! As you said, either way, very interesting.

LikeLike

Linda,

Interesting take on the survey parties. In a way they were three short versions of the Lewis and Clark expedition. They traveled some pretty dangerous country. In the end the route choice was an economic decision driven by business interests in Chicago and St. Louis. Geography had very little to do with it.

Paul

LikeLike

Karen,

Thanks for the kind words. So far, no one has called it old hat. Now if somebody like Paul Hutton weighed in that might change, but for those of us who aren’t graduate historians it seems like it might be a new slant. Hope to see you at WWA.

Paul

LikeLike

The central/southern contention over the route for the transcontinental railroad was prefigured by a dispute over the route for the Butterfield Overland Mail – which went from St. Louis down through Texas, and the territories to California. The postmaster at the time the mail contract was awarded was a Tennessean, who favored the southern route because it would avoid the horrible winter conditions on the central route between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. Butterfield’s service lasted barely three years, and the secession of many states along its route meant that Congress revoked the contract, even before Ft. Sumter was fired on. The central route won by default, when it came to shipping mail and passengers west, once the war began.

Another interesting tid-bit; within two or three years after the war, the transcontinental railroad had advanced far enough into Kansas that Texas cattle could be brought north without venturing into well-settled areas along the Mississippi-Missouri where they unfortunately spread tick fever to cattle there. The very fact that there were no local cattle to infect in Kansas meant that Texas ranchers could drive herds north, directly to the advancing railheads and thence loaded onto rail cars and taken directly to the slaughterhouses in Chicago – without spreading tick fever. There was a glut of cattle in Texas, at that time – and a lot of ranchers desperate to earn money and rebuild after the war. Up until that time, pork was the usual meat of choice on American tables – not beef so much.

LikeLike

Wow, Celia, how totally fascinating. I knew, of course, about the glut of cattle in TX and the trails going to depots in KS (since that has to do with the golden age of the cowboy which is my area of research) but your clarifications on the route of the TRR are very enlightening. Thanks so much for adding to this discussion.

LikeLike

Celia,

Great stuff. Thank you. So tick fever turned the page on one of the most colorful chapters in American History. Who knew? A preference for Jeff Davis’ southern route based on weather considerations certainly makes sense- Andi’s picture is worth a thousand words. Snow bound trains were not uncommon in winter. I’m kind of bummed about the spring we are having, but it’s better than being snow bound on a 19th train in the middle of…….well in the middle. Thanks again.

Paul

LikeLike

awesome, hope to hear more from you

LikeLike